Musings on the nature of Absolute Good and Evil.

"Are there, infinitely varying with each individual, inbred forces of Good and Evil in all of us, deep down below the reach of mortal encouragement and mortal repression — hidden Good and hidden Evil, both alike at the mercy of the liberating opportunity and the sufficient temptation?" — Wilkie Collins.

"Are there, infinitely varying with each individual, inbred forces of Good and Evil in all of us, deep down below the reach of mortal encouragement and mortal repression — hidden Good and hidden Evil, both alike at the mercy of the liberating opportunity and the sufficient temptation?" — Wilkie Collins.

|

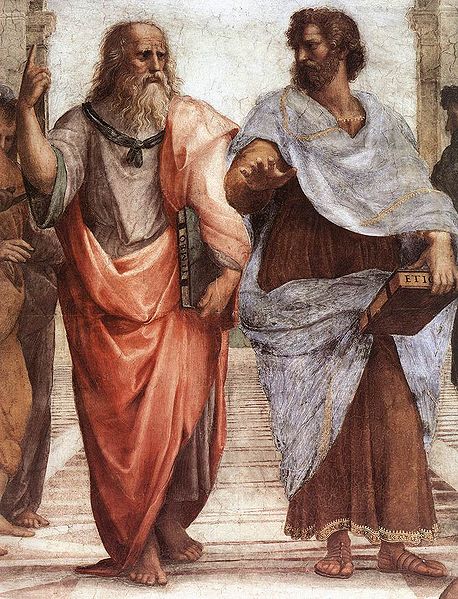

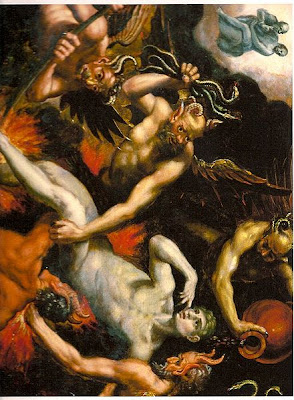

| Absolute Good vs. Absolute Evil. (Satan before the Lord, Corrado Giaquinto.) |

|

| Immanuel Kant |

The big question is whether there is absolute Good and Evil, although it’s part of a bigger question — if so why? Whetstone for human spirit? For the thrill of it? Is it a local phenomenon or it’s valid for the rest of the universe(s)? But that’s like asking WHY God exists. Makes the mind boggle. I’m afraid we’ll have to settle for the answer 'Because He Does' in the foreseeable future.

Back to the original question, since the dawn of time philosophers have been trying to find a meaningful answer to this pivotal issue.

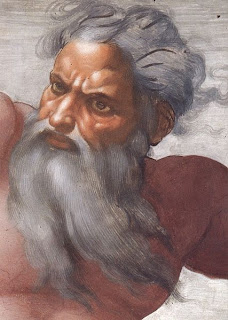

According to Plato the eternal verities, the Ideas or Ideals, are comprehended by dialectic in the light of the Idea of the Good.

“Rising of the soul into the world of mind. In the world of the known, above all is the idea of the Good.”

|

| Plato |

“That which provides their truth to the things known (as sun helps to see, linking the sense of sight and the power of being seen), and gives the power of knowing to the knower is the idea or principle of Good and is the cause of understanding and of truth, which as we know them are both beautiful, so it (Good) is something different, something still more beautiful than these. The eternal nature of the Good must be allowed a yet higher value (than truth and knowledge).

With things known, the Good is not only the cause of their becoming known, but the cause that knowledge exists and of the state of knowledge (the cause of their state of being , though the Good is not itself a state of being), although the Good is not itself a state of knowledge, but something transcending far beyond it in dignity and power.” (Plato, Republic. Book VII)

In other words, Plato sees the idea of the Good as the primal Deity (ultimate reality) that grants understanding and truth, notions preconceived (considered) as undebatably positive. One can logically deduce that, abstractly speaking, anything that hinders the flow of “the power of knowing to the knower” should be considered negative.

I hold Plato as objective idealist, who believed that (ideal) Forms or Ideas have their own independent existence, of which we like prisoners in his Allegory of the Cave only perceive projections (shadows) in our reality.

Allegory of the Cave is an imaginable scenario in which a group of people is chained in a cave all their lives, facing a blank wall and watching shadows projected on the wall by things passing in front of a fire behind them. All they can do is ascribe forms to these shadows that are as close as they get to seeing reality. The philosopher, according to Plato is like a prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall are not the reality itself but its reflection, as he can perceive the true form of reality rather than the mere shadows seen by the prisoners. Thus what prisoners conceive as real is in fact an illusion. (Pretty much like in ‘Matrix’).

Plato’s concept of Forms is in tune with Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, Aristotle's God, which is especially close to my heart. (The Unmoved Mover is perfectly beautiful, indivisible, and contemplates only the perfect activity: the process of Its own contemplation.)

|

| Plato and Aristotle, (Rafaello Sanzio). |

He based his ethical theory on this teleological worldview. Because of his Form, a human being has certain abilities. Hence, his purpose in life is to exercise those abilities to the uttermost. So the most characteristic human ability, which is not included in the Form of any other organism, is the ability to think creatively. Therefore, the best human life is a life lived rationally (and can be considered absolute good).

However, to this day a question still persists: how can one know what is truly Real and Good? How can we distinguish absolute Good and Evil from its projection in our world, that is, right and wrong?

|

| Aristotle (Palazzo Altemps, Rome) |

in other words, I believe that

— there exist objective facts/concepts of morality (moral realism),

— that the ideas of right and wrong are intuitive,

— and some moral truths can be known without inference,

— we sometimes have intuitive awareness of value that our ethical knowledge is based on.

To sum up,

Intuitivism: Moral concepts can’t be defined through experience and reason, they are conceived intuitively as self-evident verities (intuitive awareness of value that our ethical knowledge is based on).

On one hand, we (or at least some of us) aren’t born as a tabula rasa (the mind in its uninformed original state) where information is eventually written through sensorial experience. Either it’s a priori knowledge encoded in our brain cells, or some moral principles implanted in our soul, the truth is it’s included in the package of our innate unchangeable nature together with character traits and personality (similar to computer hardware).

The uncertain definition of the quantum world is probably a reflection of the elusiveness of absolute verities and God.

However, I’ve always tried to find some scientific foundation (or at least some association with science) for intuitively perceived concepts.

Speaking in terms of physics, the universe hinges on physical constants, the hidden counterpart of which may be the concept of absolute Good and Evil. The speed of light in vacuum, for instance, is constant for observers in all frames of reference, but varies depending on the index of refraction of the medium, just like absolute values may fluctuate in certain contexts.

Imagine what would happen if the constants started to change?'A plant, an animal, the regular order of nature — probably also the disposition of the whole universe — give manifest evidence that they are possible only by means of and according to Ideas; that, indeed, no one creature, under the individual conditions of its existence, perfectly harmonizes with the idea of the most perfect of its kind — just as little as man with the idea of humanity, which nevertheless he bears in his soul as the archetypal standard of his actions; that, notwithstanding, these ideas are in the highest sense individually, unchangeably, and completely determined, and are the original causes of things; and that the totality of connected objects in the universe is alone fully adequate to that Idea.'

(Immanuel Kant)

The cardinal argument in favour of the existence of absolute principles, and therefore God, is this rigid and inexorably infrangible order of things that like a diamond crystal lodges scourges such as diseases, aging and death in points of its lattice, and in which we, together with the rest of living things, are trapped like moths in a cobweb.

"…the universe is governed by the laws of science. The laws may have been decreed by God, but God does not intervene to break the laws." (S. Hawking)Why indeed do we age, get ill and die?

Why do the illnesses exist?

Couldn’t we at least simply expire without a harrowing agony? Why certain actions lead to diseases?

Why does pain and suffering exist?

Why can crocodiles (apart from their obvious superiority to us in physical qualities), parrots and tortoises live more than 100 years without showing any visible signs of aging, and sequoias up to 4000 years bordering on immortality, while humans take forever to grow up and start to wither shortly afterwards at about 25? Isn’t it humiliating?

Why do most of our inventions contaminate the environment and ultimately prove harmful to ourselves?

Why do almost all synthetic medicaments have side effects and don’t really cure anything?

And so on.

The answer “because they do” doesn’t do for me.

And so on.

The answer “because they do” doesn’t do for me.

Is it because we go against some universal principles?

Are we breaching the laws of Nature?

One thing is for certain, we are on the wrong path.

Back to earth, what would be the definitions of absolute evil? It’s impossible to describe the infinite palette of individual cases in one phrase, but here goes one of the reasonable postulates I can think of:

To illustrate my point — fanaticism, paedophilia, rape, cruelty to animals, fossil fuels in the long run, and the like are at the top of my personal list of absolute evils, and no good deeds can possibly make up for these wrongs (especially from the victims’ point of view).

Although difficult to categorise some concepts are universal truths — granted, sometimes the boundaries between right and wrong are blurred — nevertheless, while in essence something may be considered absolute evil, in practice individual cases can be justifiable, inevitable, forgivable or lesser evil. For example, burglary, mugging, larceny, embezzlement and the like can be arguably justified, if a person commits them out of hunger or similar circumstances, but should be regarded as iniquitous when perpetrated out of pure greed. However, that doesn't change the (negative in this case) nature of the deed in itself. Note that "absolute" doesn't mean the extreme degree, but rather positivity of the quality of being good or evil.

Absolute Good and Evil is a point of reference for each individual case, a moral being’s lodestar, an ideal mathematical abstraction of the real world.

Still, individual cases should be judged by approximations of absolutes, rather than by absolutes themselves.

As for me, a simple question helps me to tell right from wrong in everyday life (not that I always act accordingly, though ;-)):

“How would you feel if what you do to others (the harm) were done to you?”

Imagine it and that's your litmus test (note: wouldn’t work for masochists and those with similar disorders).

'So act that your principle of action might safely be made a law for the whole world.' — Immanuel Kant

Absolute verities aren’t conceived, but perceived ideas – the hidden essence of the universe. Precisely the belief in absolute truths should make us question conventionalities, societal norms and laws.

Virtue in distress, and vice in triumph

Make atheists of mankind. — Dryden.

Make atheists of mankind. — Dryden.

Not surprisingly, all too many people tend to deny the existence of absolute morality and instead go by Einstein’s “Morality is Purely a Human Matter” and, therefore, relative.

"I do not believe in immortality of the individual, and I consider ethics to be an exclusively human concern with no superhuman authority behind it."

A. Einstein. The Human Side.

A. Einstein. The Human Side.

As a matter of fact it’s comforting to believe there is no such thing as absolute good and evil — deep down, those who profess this belief feel they can't live up to such high standards and instead seek to get rid of or abolish the Damoclean sword of the sense or concept of guilt and retaliation in kind. That’s what made Communism so attractive to the uncultured masses:

"God doesn't exist and anything goes".

Far be it from me “to set myself up as a judge of Truth and Knowledge” — my “absolutes” might well prove to be mere illusion someday — but that’s what I make of this world.

To my eye, an amorality in itself, relative morality is a perfect breeding ground for hypocrisy, conformism, and comes down to squaring your evildoings with your conscience. It poses questions along the lines of:

—What are then the criteria to base our judgement of right and wrong? The Procrustean bed of the laws laid down by the strongest and the vilest for the meek to obey?

— What makes one point of view preferable to another apart from the power of imposition?

— Who decides and on what grounds who has rights and who doesn’t?

— If we don’t believe in God that will judge us, what stops us from committing any crime as long as we manage to get off scot-free?

Besides, from the wrongdoer's standpoint it won’t be a crime at all.

— If someone considers you don’t have the right to live, what makes you right and them wrong?

In the realm of relative morality all values are relative as well, there’s no justice or injustice, but different viewpoints. Anyway, what use is morality? After all, animals have survived without it for millions of years and will probably outlive us.

Ideas of relativity of ethics are usually used to justify heinous crimes. By that logic Hitler and Stalin can be considered simple fumigators, and slaveholding societies justified slavery by the inferiority of certain races (oblivious to the slaves of their own race, past and present).

Rather than just keep us from devouring each other out of fear of divine punishment, absolute values should inspire us to do our best and make the most of our lives.

Einstein’s musings on ethics could serve as an example of relative-morality creed, notwithstanding that he wasn’t a true atheist, but rather an agnostic.

|

| Albert Einstein (1921) |

|

| Personal God |

The scientist is possessed by the sense of universal causation... There is nothing divine about morality; it is a purely human affair. His religious feeling takes the form of a rapturous amazement at the harmony of natural law, which reveals an intelligence of such superiority that, compared with it, all the systematic thinking and acting of human beings is an utterly insignificant reflection... It is beyond question closely akin to that which has possessed the religious geniuses of all ages.'

Albert Einstein, The World As I See It (1949)

There’s no better answer to this than E. Kant’s words: “God without morality is fearsome”, and that’s Einstein’s God.

To believe that absolute good and evil are inextricably linked to intelligent species is a telling example of human species' hubris. Especially considering it’s coming from beings that can’t even control their inner workings.

Shall I point out that for a man who was a lousy sexist husband, hardly ever crediting his wife’s contribution to his work, and even worse father (that had almost no relationship with his two sons, one of them a schizophrenic, and got rid of his illegitimate firstborn daughter), whether it was justifiable or not (not that I’m criticising or being judgemental, I’m just trying to illustrate my point), it’s highly convenient to deny God “who makes demands of us and who takes an interest in us as individuals” and “declare morality a purely human matter”? Then why is morality so “important in the human sphere”? How about those who think it isn’t?

If God takes no interest in us as individuals, why does the individuality exist?

Why not create another species of insects like ants or bees instead?

Actually, human existence on this planet has no meaning, other than the realization of the only two features that make us different from the rest of animals — morality and artistic creativity.

'Two things awe me most, the starry sky above me and the moral law within me.'

Immanuel Kant

It’s curious how even such a great mind often contradicted himself. Although he made no bones about his vehement aversion towards war, patriotism and the military in general that a sage would profess, to which by the way I subscribe,

'He who joyfully marches to music rank and file, has already earned my contempt. He has been given a large brain by mistake, since for him the spinal cord would surely suffice. This disgrace to civilization should be done away with at once. Heroism at command, how violently I hate all this, how despicable and ignoble war is; I would rather be torn to shreds than be a part of so base an action. It is my conviction that killing under the cloak of war is nothing but an act of murder.'

A. Einstein.

it didn’t stop him from contributing to the creation of the most powerful weapon of the mass destruction (Project Manhattan), giving it into the hands of those he despised and “who joyfully march to music rank and file”, that eventually killed and is still killing thousands of innocent people. I wonder how he slept at nights. For some unaccountable reason the option of “being torn to shreds” passed out of his memory.

It raises a question, though, would he have taken the trouble to push the A-bomb, thus betraying his own “conviction that killing under the cloak of war is nothing but an act of murder”, if instead of Jews Hitler had exterminated only gypsies and the like? Granted, he’d argue it was conceived as a deterrent, but I would think such profound naivety would be unbecoming and even reprehensible for a Nobel prize winner.

(BTW, right after writing these lines I watched Fringe’s episode, “The Box”, in which Dr. Bishop wonders how Oppenheimer slept at nights after his invention had killed thousands in a split second. Great minds think alike!)

To his credit, he deeply regretted it by the end of his life.

'I made one great mistake in my life - when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification - the danger that the Germans would make them...' (A. Einstein)

We always find justification for our actions, don't we? But did it undo the harm or make the victims feel any better?

We always find justification for our actions, don't we? But did it undo the harm or make the victims feel any better?

No wonder he needed to get rid of the concept of divine punishment to silence the still, small voice.

'The release of atom power has changed everything except our way of thinking...the solution to this problem lies in the heart of mankind. If only I had known, I should have become a watchmaker.' (A. Einstein)

Yea, probably he should have. It’s hard to believe such a great mind was so ingenuous as to not have known that if our way of thinking hasn't changed for 6000 years, it wasn't going to do so in barely 100 years. Science doesn't civilize human apes, it just makes them more dangerous and destructive.

The truth of the matter is, what he tried to do was stretch his theory of relativity far beyond the realm of science, where it falls apart.

The truth of the matter is, what he tried to do was stretch his theory of relativity far beyond the realm of science, where it falls apart.

The difference between relative and absolute morality is along the lines of

'Theist and Atheist: The fight between them is as to whether God shall be called God or shall have some other name' [Samuel Butler Note-books].

To put it simply, relative morality: whatever I do is not evil in my frame of reference even though it seems otherwise from yours (we are both right and wrong at the same time).

Conversely, absolute morality suggests that even though I believe what I do is not evil in my frame of reference and may sometimes be justified, forgiven, lesser evil etc, none of these can undo the harm or change the nature of the wrongdoing, and will therefore always be absolute evil regardless frame of reference.

'I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings.'

Albert Einstein, Albert Einstein: The Human Side

What if He does “concern himself with the fates and actions of human beings”?

How can he or anyone know what God concerns himself with? Could Einstein verify if God he believed in is exactly as he, Einstein, imagined Him to be or a personal God of “feeble souls” who believe “the individual survives the death of his body through fear or ridiculous egotisms”?

Isn’t it that one way or another we all profess some kind of blind faith?

"You cannot plumb the depths of the human heart, nor find out what a man is thinking; how do you expect to search out God, who made all these things, and find out his mind or comprehend his thoughts?"

Apocrypha: Judith

Apocrypha: Judith

It should be taken into account, though, that he and Spinoza were both Jews, and as such probably felt subconsciously uncomfortable with Christian God for obvious reasons. For someone who rightly scorned patriotism, his earthly concern with Jewish identity is somewhat surprising.

'Heroism on command, senseless violence, and all the loathsome nonsense that goes by the name of patriotism — how passionately I hate them!' — A. Einstein

Is there anything more relieving than to believe that for God “all the systematic thinking and acting of human beings is an utterly insignificant reflection”, so whatever crime we commit is insignificant for God, and the only thing left to worry about is getting away with it?

While I couldn’t agree more that fear of punishment and hope for reward are no basis for true morality, and make us rather slavishly obedient to the Divine whip, than virtuous,

'If people are good only because they fear punishment, and hope for reward, then we are a sorry lot indeed. The further the spiritual evolution of mankind advances, the more certain it seems to me that the path to genuine religiosity does not lie through the fear of life, and the fear of death, and blind faith, but through striving after rational knowledge.' — A. Einstein, The Human Side.

there’s no doubt it serves to keep the people without criteria of their own or scruples, and therefore society in general, at bay.

‘Everything good that is not based on a morally good disposition, however, is nothing but pretence and glittering misery.’

Immanuel Kant.

As an antithesis, however, what’s the use of being good if there’s neither reward for being good nor punishment for being evil?

What’s more, in our world mostly those without morals succeed. “Ethical behaviour is regarded as an affliction to be pitied, a loser’s burden. Without conscience there can be no trust. Without a shared moral code there can be no free society.” (Daily Telegraph)

What’s more, in our world mostly those without morals succeed. “Ethical behaviour is regarded as an affliction to be pitied, a loser’s burden. Without conscience there can be no trust. Without a shared moral code there can be no free society.” (Daily Telegraph)

But what moral code do we agree to share? Einstein’s? Mine? Yours?

What makes mine preferable to yours and vice versa?

Wouldn’t we be better off sticking to the universal code based on absolute truths that no one can argue against?

|

| Torment of Hell |

‘[A scientist] has no use for the religion of fear and equally little for social or moral religion. A God who rewards and punishes is inconceivable to him for the simple reason that a man's actions are determined by necessity, external and internal, so that in God's eyes he cannot be responsible, any more than an inanimate object is responsible for the motions it undergoes. Science has therefore been charged with undermining morality, but the charge is unjust. A man's ethical behaviour should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties and needs; no religious basis is necessary. Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death.’

Albert Einstein, "Religion and Science," New York Times Magazine, November 9, 1930

In part it’s certainly true “that a man's actions are determined by necessity, external and internal” , but a mathematical ideal shouldn’t be confused with the rough approximations. Such a statement can’t be considered either categorically true or false, but rather, we should allow for degrees of truthfulness and falsehood. There’s always a little margin between necessity and choice, like an infinitely-tending-to-zero distance between a curve and its asymptote.

On the other hand it’s a perfect apology for any irresponsible and immoral action in the name of science. Inanimate objects don’t possess minds or the ability to reason and make decisions that affect the surrounding world. According to Einstein human beings are mere programmed biological machines endowed with neither intellect nor will of their own, (which makes them even inferior to the rest of the animals), and can’t therefore help committing whatever knavery they’re up to.

I have to acknowledge the lure of the worldview that lets you shuffle off any sense of responsibility or guilt is so strong that it’s managed to win over most part of the world population, but my gut feeling tells me that it sounds too good and simple to be true.

Besides, why do we suffer if God can’t hold us responsible for our actions?

What’s the reason of such blatant injustice?

Then again, how did Einstein know whether we can or can’t be responsible in God’s eyes?

Did he experience some kind of epiphany or a spiritual flash? Nope, he just decided so.

What I’m at a loss to understand is why animals suffer, since they’re clearly free of guilt. (Well, the only logical explanation that occurs to me is that they might have been evil or devolving humans in their past lives. Not that I like the idea, but there’s some logic to it.)

I wonder if Einstein ever argued for shutting down prisons and abolishing laws.

Is it ethical for human beings to punish their fellow men whose “actions are determined by necessity, external and internal” , despite the fact that even “in God’s eyes they cannot be responsible”?

What should those who got little or no sympathy for or with anything but money, have received little or no education at all, and view social ties and needs as a mere means of self-preservation (and with a good reason) base their ethical behaviour on?

Probably the same pillars BP CEOs or those responsible for the Hungarian toxic spill to name but few, base their moral creed on (about three months ago they already knew there were cracks in the wall of the reservoir filled with toxic sludge but didn’t do anything to prevent the catastrophe. Plus, the wall was built of the recycled low quality materials. Why would they care? They aren’t among those 7 casualties, it’s not their houses and lands that have been swept away by toxic sludge, nor do they have to clean up the mess!).

What “external or internal necessity" goaded the scientists, who have “no use for the religion of fear and equally little for social or moral religion”, into making such valuable contributions to the welfare of humankind as DDT, Asbestos, mad cows, Chernobyl, Nukes, gender-bending chemicals, biological weapons, fossil combustibles, food stuffed with hormones and antibiotics, Bhopal, killer bees? And the list goes on.

Since “a God who rewards and punishes is inconceivable to them” they don’t feel responsible for their actions — without doubt a great consolation for the victims. Strangely enough, those who can’t distinguish between right and wrong and can’t control themselves are usually declared non compos mentis (bereft of reason) in court.

The truth of the matter is, even the greatest minds can err — Einstein said about quantum mechanics, ‘this theory reminds me a little of the system of delusions of an exceedingly intelligent paranoiac, concocted of incoherent elements of thoughts’.

|

| A. Einstein and N. Bohr |

‘I am convinced that He (God) does not play dice,’ he claimed in one of his famous conversations with N. Bohr. (Then again, how can anyone know for sure what God plays?)

‘And who are you to tell God what He should or shouldn’t play?’ retorted Bohr.

Delusional or not, so far quantum physics hasn't provided answers to such transcendental questions as

'— What is mind and matter?

— Of them, which is of greater importance?

— Is the universe moving towards a goal?

— What is man's position?

— Of them, which is of greater importance?

— Is the universe moving towards a goal?

— What is man's position?

— Is there living that is noble?'

because of the limitations of its instruments. That’s where quantum mysticism takes up, “its conquests are those of the mind”.

Then again, that sounds like religion.

Then again, that sounds like religion.

To wrap up this long-winded and profound intellectual disquisition: much as many people insist on arguing to the contrary, everyone has his/her personal God.

As for me, I believe in God that created this beautiful, but cruel world and inspired the greatest masterpieces of art.

(You can ask your questions, submit answers and vote on the answers you think are the best in the Get Answers gadget below the posts. Just sign in first with GFC (the 'Follow' button) right above the gadget.)

"Shall I point out that for a man who was a lousy sexist husband, hardly ever crediting his wife’s contribution to his work, and even worse father (that had almost no relationship with his two sons, one of them a schizophrenic, and got rid of his illegitimate firstborn daughter)..."

ReplyDeleteAlmost all of this is completely untrue, especially that his first wife made contributions to his scientific work.

Allen,

ReplyDeleteall my statements are based on printed books, documentaries and scientific publications (and not the Internet sources) that draw upon official records and the reports of contemporary witnesses and historians’ research.

I usually rely on well-documented facts (e.g., obviously something weird happened to his daughter), now, I can’t possibly verify whether the information these sources provide is false or not. On the other hand, men are usually prone to play down women’s contribution to men’s work.

Einstein himself confessed he wasn’t very good at maths.

Unless you knew Einstein and his wife personally or can communicate with the dead, you can’t claim all this is positively untrue.